WHEN VICE PRESIDENT JOE BIDEN compared New York City’s LaGuardia Airport to a “third-world country,” suggesting that if he blindfolded somebody and dropped them in a middle of a terminal, they wouldn’t believe they were in a modern transportation facility, he struck upon an issue that perplexes travelers from the United States, especially those who spend significant time overseas. How has our country’s airport infrastructure fallen so far behind? While it may seem that Americans don’t often agree on things—especially during an election season—one issue that unites everyone is a general distaste for air travel, from constant delays and cramped seating to crumbling facilities and TSA security lines that move at a glacial pace.

Across the world, newer airport facilities, such as Changi in Singapore or Schiphol in Amsterdam, look like the breezy, sleek future of air travel envisioned in midcentury travel advertising. Back in the United States, however, air travel, especially during the summer, can often feel as glamorous as being packed into a crowded subway car during rush hour, with even less personal space.

While nobody likes the drawn-out experience of boarding a plane—Devin Liddell, principal brand strategist at Teague, a Seattle-based design consultancy, says many simply view airports as “a series of lines that leads into one another”—there’s more than time on the line. The per-minute cost of delays to U.S. airlines in 2014 was $9.1 billion, in part caused by the inefficiency of funneling passengers through crowded airports. As the number of passengers continues to multiply—trade group Airlines for America expects the volume of flyers to hit an all-time-high this year—fixing the our flight system becomes a vital economic issue. These key pieces of infrastructure also offer a massive design challenge. Curbed spoke to five designers and consultants who specialize in airport design to help understand why the system seems broken, and how smart design can help.

Aviation History and How We Got Here

It’s natural to complain about airports after having a poor flying experience. But adding insult to injury by comparing U.S. airports to newer terminals around the world isn’t necessarily a fair comparison. Our airports have their own unique history and issues, that make judging, say, New York’s infamous LaGuardia by the standards set at new airports in Dubai and Singapore an unfair comparison.

“That expectation can lead to an unfair critique of the U.S. aviation system,” says Derrick Choi, a principal and aviation designer at Populous. “It goes back to history. The U.S. was an early adapter of aviation, and invested in a lot of terminals in the decades before and after WWII. So it’s not surprising we’re going through rough times in terms of modernising, as well as adapting to post-9/11 security requirements. Emerging markets and countries are pinning their future hopes on these amazing, brand new gateways, while in the U.S., we’re in the midst of reconstruction.”

The long lifespan of many U.S. airports, and the wide acceptance of flight as a regular mode of travel, has turned formerly glamourous airports into overloaded, everyday infrastructure, that wasn’t meant to handle the increasing number of passengers, bags, and flights required by the growth of modern aviation. They’re looked at “almost like a bus service,” says James Park, founder and principal of JPA Designs, a firm that focuses on aerospace and rail design. The response, more often than not, has been a patchwork of expansions and additions, instead of a wholesale overhaul or redesign. The noise, pollution, and cost associated with enlarging airport facilities, as well as local opposition to expanding the footprint of these facilities, often make the idea a non-starter.

“Dubai’s airport is a statement of prominence that establishes them on the world stage,” says Ty Osbaugh, leader of the global aviation design practice at Gensler. “It’s a status symbol, while in the United States, we’re more about functionality. Look at the comparables in volume. Dubai’s airport is expected to handle 25-30 million passengers per terminal per year, and each stretches out over about 7 million square feet. The JetBlue Terminal at JFK Airport in New York handles about 22 million passengers a year, all in a space that’s less than one million square feet. They’re looking at space and amenities, while we’re looking to get in and out as quickly as possible.”

If those aren’t enough hurdles standing in the way of modernization, the ownership and control structure of airports in this country also impedes change.

“U.S. airports differ quite a bit from others in the rest of the world in that there isn’t a clear leader who owns the experience,” says Liddell. “The relationship between the airport authorities and airlines is sort of like a landlord-tenant model. There’s only so much one entity can do.”

How to Improve Layout and Architecture

With a limit on space, and the huge challenge of replacing legacy facilities, airport designers and architects in the United States are often left with limited options to make passenger flow, function better: make better use of the space you have, or build up, not out. Often, that reimagining process begins with the check-in process.

According to Osbaugh, Gensler believes vertical expansion may help ease overcrowding and simplify traffic flow. Placing security and check-in on two different floors, as the company proposed for a redesign of JetBlue’s T5 Terminal at New York’s JFK airport, will help organize traffic flow. Passengers break down into two main groups: high-tech, who navigate check-in with the help of mobile technology, and high-touch, those who need extra service and help to make their way to their flight. By separating passengers at the curb when they arrive, high-tech flyers can check in on one level, while high-touch travelers have an easier time finding assistance. They only meet in the security lines.

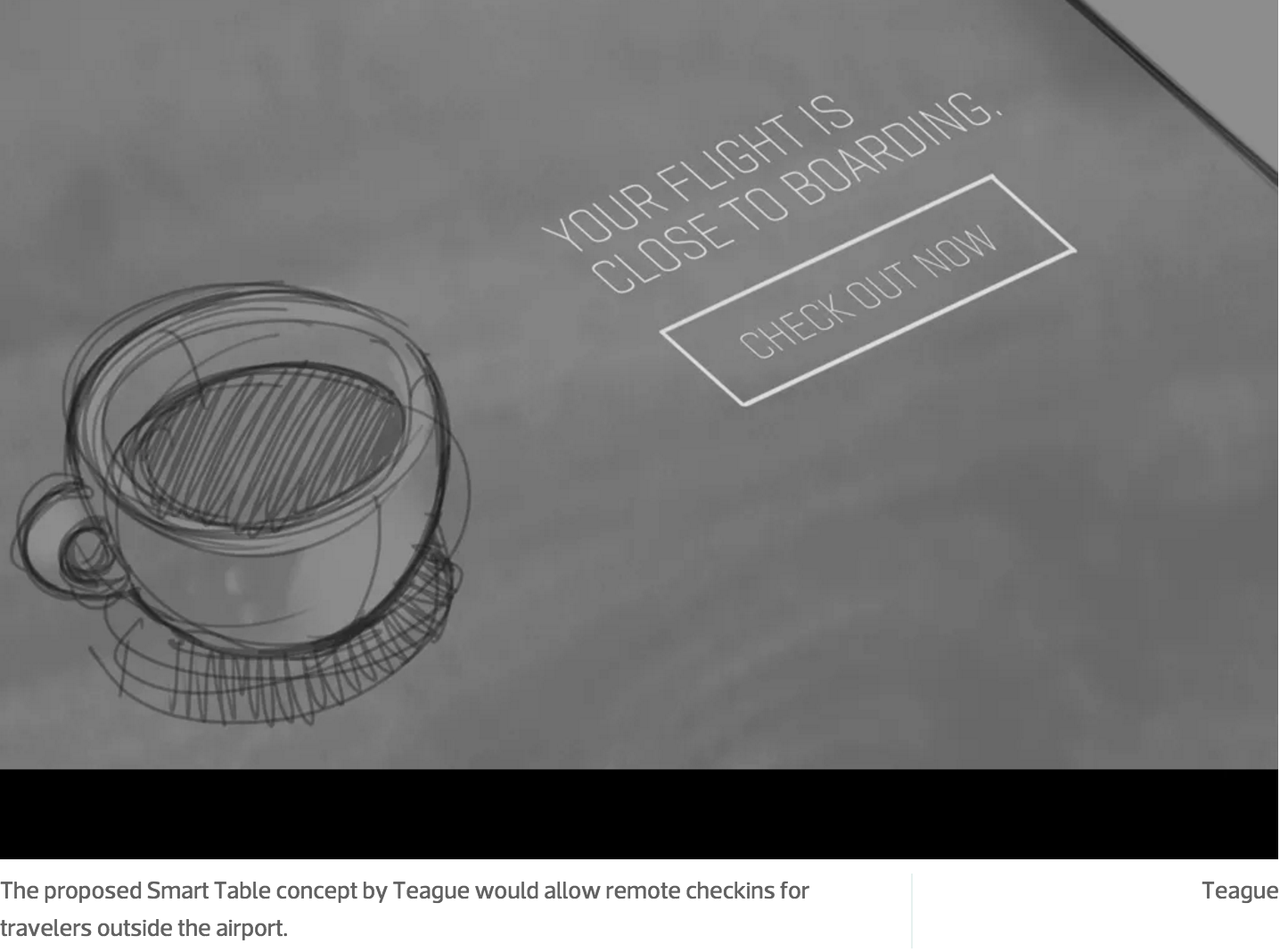

Others believes that as mobile technology becomes even more ever-present, it enables carriers to push the check-in process outside of the airport itself. Liddell imagines creating satellite check-in spaces at hotels and other traveler checkpoints to create a meaningful extension of the airport footprint. Plenty of companies, such as Airbnb and Uber, have transformed their industries with software; why can’t airlines continue to develop remote means of verifying and directing passengers?

Many have already started. Dwight Pullen, senior vice president and head of the Aviation Center of Excellence at Skanska, brings up the example of Alaska Airlines in Seattle, which has created a flexible check in space, where the entrance can be quickly repurposed for different needs and travel periods, and instituted a program to print bag tags at home, allowing travelers to just walk in, toss their bags on a belt, and head to security.

“The days of just seeing a horizontal row of check-in spots is going away,” says Pullen. “Of course, you need the space within a terminal to configure your systems to accommodate this.”

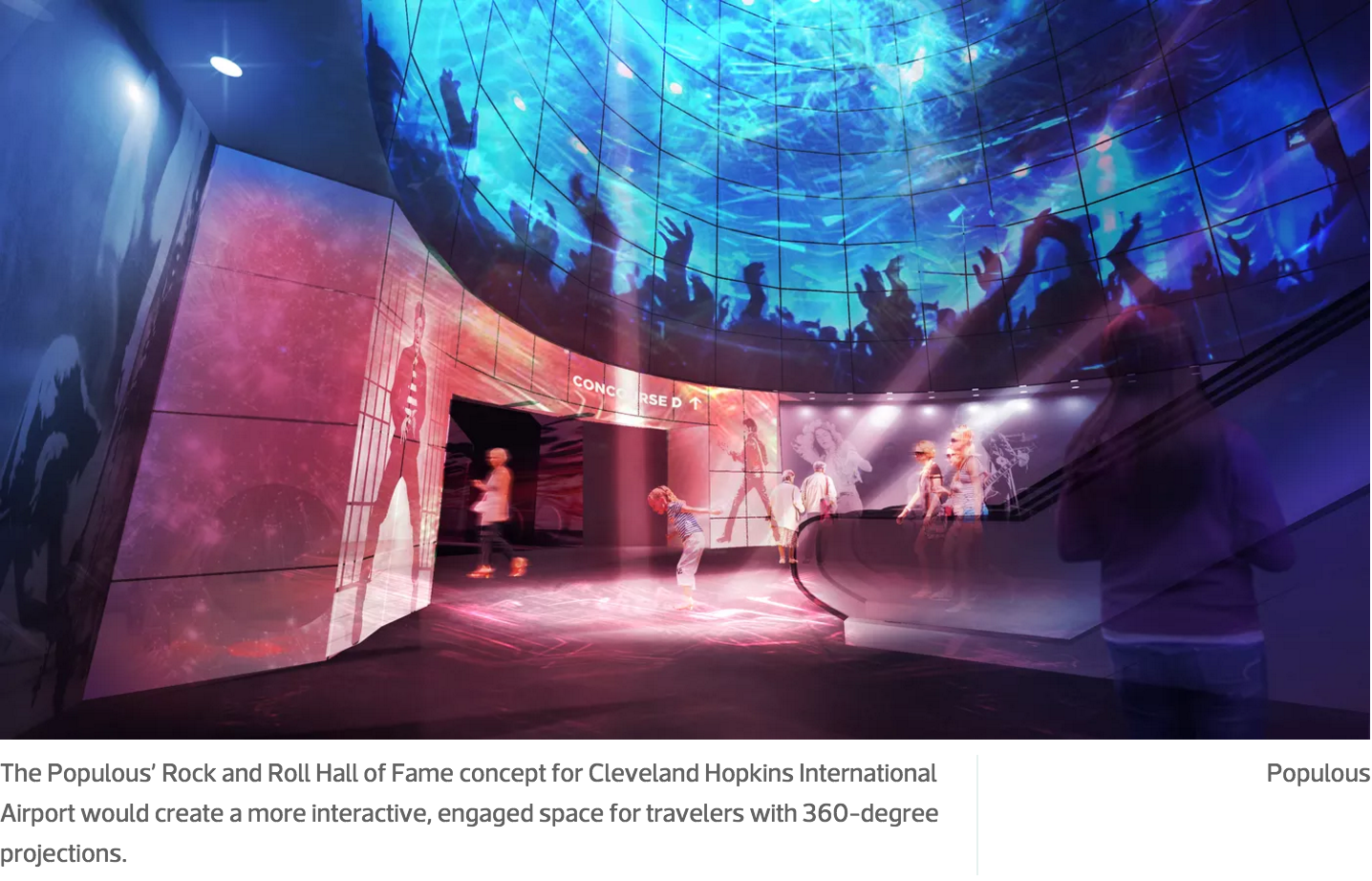

Flexible space design becomes imperative, especially with changing security needs and new technology shifting how airlines interact with passengers. Choi says Populous has been experimenting with numerous ways to activate flexible and empty spaces in airports, from retail and performance spaces to bringing in local food trucks to the terminal, all in an effort to engage travelers and help utilize any existing real estate.

Lost and Found: The Need For Better Wayfinding

“Passengers are increasingly looking for a seamless experience,” says Choi. “Many places don’t have the space or resources for a complete overhaul, so there’s a lot of research going into seamless check-ins, offsite check-in, wayfinding, and other ways to improve the passenger experience.”

Airport designers are increasingly turning to better communication, signage, and technology to make passenger flow more efficient, eliminate the feeling of being in a funnel, and the navigation process as straightforward as possible. Many designers see the increase in mobile and beacon technology (a series of sensors that identifies where a user is within a building at any moment), as a way to make moving through an airport simpler and snappier. Apps could direct users to the shortest security line, or alert them exactly when they should begin to head to their flight to board, instead of forcing everyone to sit and stew in overcrowded gates.

“We should reimagine the airport around smart space,” says Liddell. “Think about how people line up now; it’s a failure of wayfinding. Everyone begins boarding at the same time, and there are bottlenecks all over the airport. We could be using technology to create virtual assistants that lead users around the airport.”

Pullen’s team considered a similar tech solution during terminal expansion at Bush International Airport in Houston, where United Airlines wanted to attempt a self-boarding system. By introducing a self-scanning system, and taking advantage of mobile boarding passes, the system could not only facilitate a more gradual, easy boarding process, eliminating confusion and crowds rushing the gate, but free up staff from scanning tickets.

“Letting the computers sort out who should be boarding when could be a way to make sure operators get the intended efficiency out of boarding,” he says. “The computer won’t care about getting people angry that it’s not their turn to board yet.”

Improving Security and Boarding Without Being Lax

Everything comes down to knowing the passenger, says Liddell, and directing and helping them with the aid of technology that’s already available. This same concept can improve what’s often seen as the worst part of the airport experience, the drudgery of TSA security lines.

“It’s unpleasant being in an environment that’s deeply suspicious of everyone,” he says. “The government is already pushing for the expansion of the pre-check program, so why not push that even further with technology? If the airport has more powerful ways to know people, you can make the experience more efficient, with remote check-ins, or RFID tags on bags that track all checked luggage. It could even help create security alerts if the system detects an unchecked bag. It would be giving up some privacy, but think of it like Amazon; you’ll gladly give up some personal data for two-day shipping.”

Having your package continually tracked may seem intrusive, but it’s actually already in use. At McCarran Airport in Las Vegas, they track all baggage via RFID antennas (and have done so for years). The increased awareness and data has helped substantially reduce lost luggage. Liddell’s firm has taken the idea further with its “bag bot concept.” A robot would deliver bags to passengers after they deplane, utilising RFID and app technology.

“Baggage claim is completely inefficient, with everyone standing around waiting for this metal monolith to belch up bags,” he says.

Pullen believes any discussion of improving security requires give and take from both the TSA and passengers. Adding more staff, as well as flexible security lanes, to allow for quicker security checks during heavy flight times, seem like no-brainers, as well as eliminating the need for domestic travelers who are switching terminals to have to go through security again at certain airports. However, there remains a heavy responsibility on the passenger.

“It’s been 10 years since the TSA banned liquids over three ounces from going through security, yet how many people are slowing the line down because they packed water bottles?” he says. “No design is going to fix that.”

There’s no doubt the experience requires a rethink. According to Osbaugh, Gensler is looking at an unlikely inspiration: Disney.

“We’re not going to implement Disney security, obviously,” he says. “But I think changing the system as it is now is going to take something like that, something just as radical, and even whimsical. The TSA isn’t focused on the passenger experience. Look at how Disney does their FastPass, which provides an assigned time for guests to enter. What if we did that with security? Then maybe we could turn ticket halls into lounges. We need to step back and look at a more holistic experience.”

What Comes Next

Technical solutions and redesigned terminals sound fantastic, but they won’t save stressed out travelers stuck in lines this summer. The travel experience is already expected to be fall below already low expectations (national news was all over reports that security lines at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport exceeded three hours late this spring). However, borrowing from the language of recovery programs, perhaps bottoming out is the only path to recovery. Nobody understands the stakes better than airports, who often bear the brunt of complaints, but haven’t had extensive control over many aspects of the airport experience. News that Delta had created its own, more efficient, security line may serve as the first of many attempts by carriers to take more control.

Osbaugh said that while Gensler was working with JetBlue, they had access to the company’s Twitter feed for consumer research, and discovered 80 percent of complaints were about security issues.

“For the past 30 years, it’s been the airports calling the shots and airlines paying rent, but now the airlines are thinking about funding their own facilities,” he says. “With more airline consolidations, we’re already starting to see it. American, United and other carriers realize they need to differentiate themselves to keep or gain market share. The question is, how do they start to creep into the security situation, and what does the TSA do?”

With the issue becoming so prominent, others see new sources of funding coming to help alleviate the issue. The multi-billion dollar LaGuardia renovation (built and managed by Skanska) will be funded via a public-private partnership, which may revolutionize how these massive projects, which usually rely on government money, get funded.

“There’s going to be a brand new model to deliver this airport,” says Choi. “It’s a watershed moment for aviation in the U.S.”

Change appears to be coming, though slow and steady may be a generous way to describe the pace. Airports and carriers understand without more capacity and better facilities, the current rates of growth are unsustainable. Liddell says they shouldn’t be complacent, or perhaps another technology will start making dents in their business. If airports don’t get smarter, he believes they’re going to be disrupted by autonomous vehicles, which could start impeding on short- and medium-range flights. It may seem unlikely now, but then again, at least travellers would have more legroom.

Article property of curbed.com

Dubai’s airport is a statement of prominence that establishes them on the world stage

Ty Osbaugh -Leader of the Global Aviation Design Practice at Gensler